An international team of archivists and historians has successfully completed the digitization and cataloging of 194 libros de hijuelas (deed books) that record statewide privatization of indigenous lands in nineteenth-century Michoacán, Mexico. The project, titled “Conserving Indigenous Memories of Land Privatisation in Mexico: Michoacán’s Libros de Hijuelas, 1719–1929,” was funded by a grant from the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme. The digital collection is now available for free at https://eap.bl.uk/project/EAP931.

According to the Endangered Archives Programme, the deed books were “endangered by environmental and political factors,” languishing “in Michoacán’s under resourced state archive, exposed to sunlight, damp, and theft, and showing clear signs of zoological infestation.”

From 2016 through 2018, the LLILAS Benson Digital Initiatives team worked with Matthew Butler (history professor, University of Texas at Austin), Brian Stauffer (historian, Texas General Land Office), Antonio Escobar Ohmstede (researcher, CIESAS), Cecilia Bautista (history professor, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo), and a team of four historians based in Morelia who were trained to digitize the deed books.

“Mexican history is populated with many myths,” says Butler, “not least indigenous people’s helplessness in the face of modernization until the revolution of 1910 ‘saved’ them. The hijuelas books are not just property records; they tell a different story of how indigenous people in Michoacán actively navigated the transition to private property and liberal citizenship, and often what they thought about the process. Thanks to the support of the British Library and the Michoacán state government, this fascinating source can now be read online, in a digital copy of the book form in which it was created but with document-level descriptions and modern search functionalities.”

Butler’s longtime collaborator, Escobar Ohmstede (CIESAS–Mexico), emphasizes the importance of the documents in counteracting “revisionist and neo-revisionist history and its interpretation of the impacts of economic, social, and political liberalism on so-called indigenous peoples in nineteenth-century Mexico and Latin America.” The libros de hijuelas, Escobar asserts, “allow us to observe in detail the way in which policies of the privatization and division of communal lands were devised, to understand their effects on small landowners as well as the ecological niches occupied by various historical actors, and to examine the conflicts that took place among indigenous communities, state, and federal authorities in response to the division of communal lands.”

Escobar and Butler agree that, in Butler’s words, “The project will offer a critical resource to historians, community activists, anthropologists, genealogists and the diaspora of michoacanos who are interested in exploring their roots.”

Theresa Polk, head of digital initiatives at LLILAS Benson, praised the collaborative effort that went into the project’s successful completion, extending her congratulations to the Morelia-based digitization team of Rocío Verduzco Sandoval, Marlen Alvarado González, Yolanda Castillo Franco, and Mayra Sujey Marín Miranda for their work digitizing and describing the collection to such a high standard, and to David Bliss of LLILAS Benson, who designed the digitization workflow, trained the team, oversaw the preservation process, and “remained a steady resource and problem-solver throughout the project.” Polk emphasized that without the teamwork and expertise of an array of staff from the University of Texas Libraries and LLILAS Benson, this project could not have come to fruition.

The culmination of this collaboration at a time when people must remain isolated from each other is bittersweet, holding the promise of future work of this kind—across borders and institutions, and in service of scholarship and learning that is accessible to people of all kinds, worldwide.

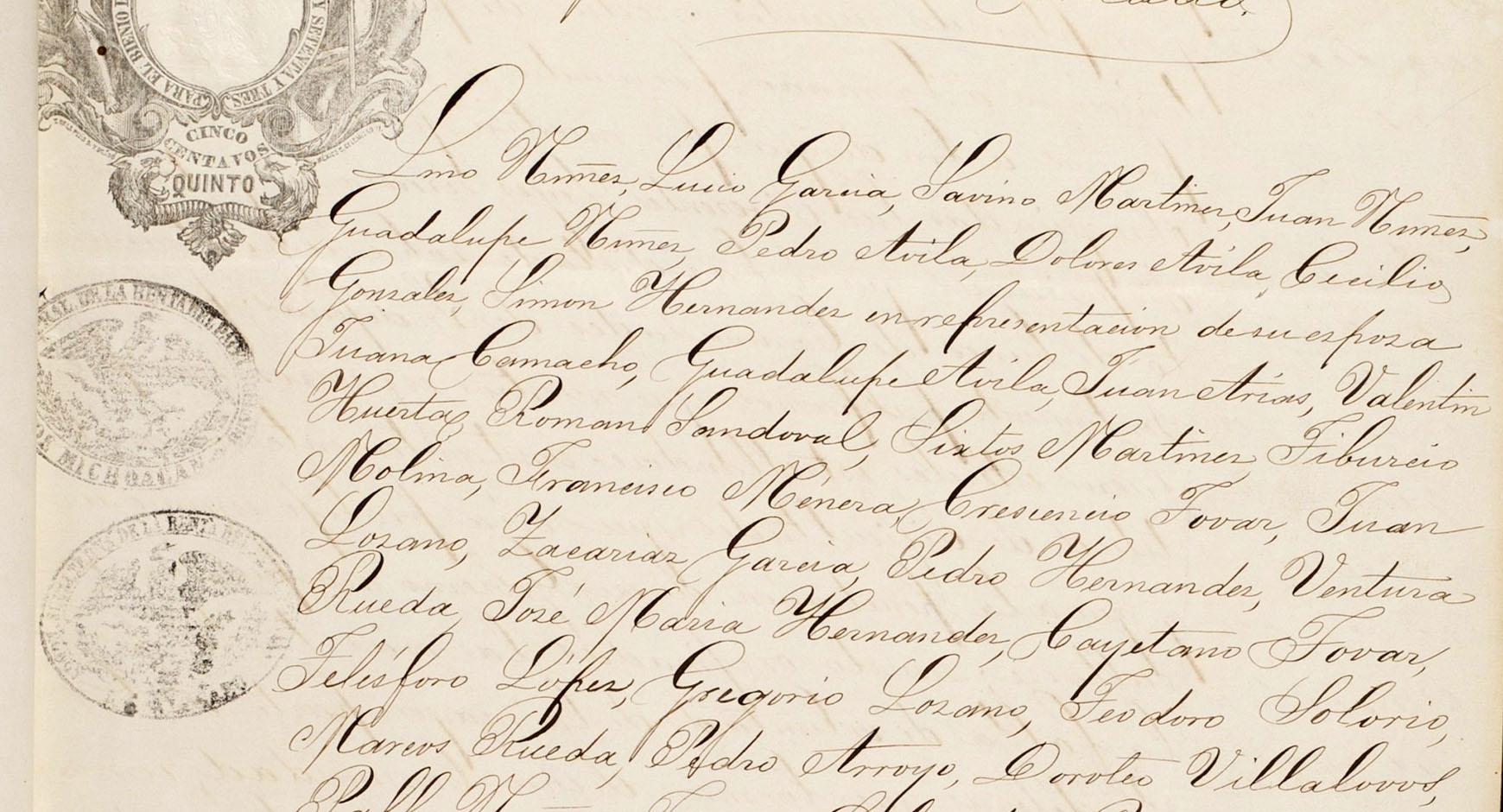

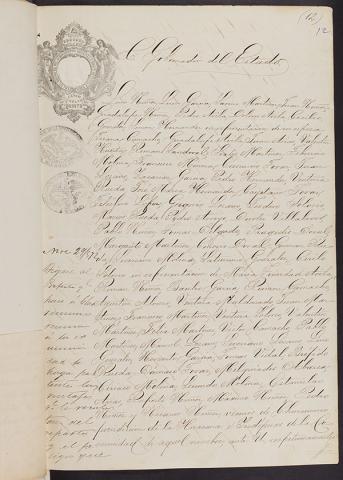

Image: Letter showing indigenous residents of Ario de Rosales, Michoacán, disputing the terms of land division in a letter to state governor Rafael Carrillo in 1872.